|

Many of us are well aware of the methods by which birds and mammals endure the winter as endothermic or warm-blooded animals needing constant food to fuel body heat. These animals move constantly, searching for food. Alternatively, others simply go into a state of hibernation to save energy when food is unavailable. Snakes, being ectothermic animals, cannot generate their own body heat, or cool themselves through sweating, and must depend on their environment to help them adjust body temperatures according to changing needs of digestion or to escape from excessive heat or cold. So, what strategies can a cold-blooded, or ectothermic animal, like a snake employ to survive the winter cold? Snakes in temperate zones of the U.S. have no alternative but to go underground, using sites called hibernacula (singular—hibernaculum) or dens, to avoid freezing. While some mammals undergo hibernation in an inactive state to conserve energy, snakes go through a similar process called brumation, but differs in that, in some cases, movements of snakes in underground dens may still occur, as they take advantage of warmer sections within the den that shift during the winter. Indeed, some prairie rattlesnakes in more northerly temperate latitudes have been known to bask outside the entrance to their underground lair at times during warm spells in the winter!

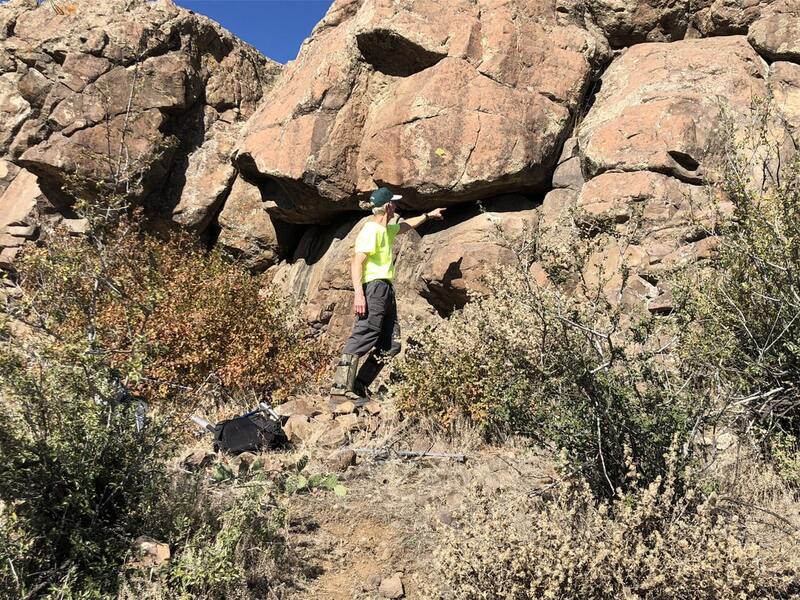

How do snakes prepare for brumation? As the day length shortens and night time temperatures drop lower, snakes sense that cold weather is approaching and begin to move towards locations that they know from experience can provide them with a way to get underground below the freezing depth. During October, snakes stop feeding in order to clear the stomach of any food, which may typically take several days. Because snakes depend on the environment to heat their bodies to the proper digestion temperature, food must be processed out before the snake becomes too cool or it will simply rot in the stomach, often leading to fatal infections. The drive to seek out den sites becomes stronger with approaching cold weather, because cold snakes lose the ability to operate muscles that control movement and are in a race against time and freezing temperatures. Some snake species move considerable distances, perhaps up to a few miles, in a migratory push to arrive at a den in time. These den sites range from ant mounds, crayfish and earthworm burrows and rodent burrows, to spaces within subterranean rock strata, tree stumps, crawl spaces, old wells, and basements, to highlight a few examples. Natural dens in the landscape are selected based on characteristics that favor maintaining den temperatures at optimum levels, like south-facing cliffs or mountain slopes where the sun heats the soil longer during the winter. The same dens may be used every year or new ones are selected, and snakes of multiple species may use the same den, because this site could be the only spot within many acres that enables these animals to successfully avoid freezing. Thus, rattlesnakes, bullsnakes, and garter snakes, among others, will use the same communal den. Even snake-eating snakes may be present, because cold temperatures eliminate the desire for feeding. The numbers of snakes using dens may be as few as 3-6 or as many as thousands, as found in Red-sided garter snake dens in Canada. Den sites also provide snakes with some security from predation, when being cold prevents defensive action, although badgers and skunks have been known to dig them out. Additionally, snakes also depend on these dens to prevent dehydration, a common cause of overwintering mortality in juveniles. Baby and juvenile snakes have a particularly difficult challenge in detecting overwintering den sites, because they don’t yet have knowledge of where they are found. These young snakes may attempt to follow the scent trails of adults to den sites or, failing that, hope that they locate some underground passage that goes below the frost line and allows them another chance in the coming year. The amount of time spent in brumation is solely dependent upon how soon the next warming cycle begins in the spring and can last 3-9 months. In less than perfect underground microclimate conditions, this time in brumation sometimes results in many snakes, especially juveniles, succumbing to skin fungus or dehydration. With the warming temperatures of early spring, underground den temperatures also begin to rise, followed by snakes gradually edging closer to the den entrance. In most species of garter snakes, emergence from brumation is essentially explosive with intense reproductive copulation taking place almost immediately. Other snakes require more time to warm up the body physiologically before moving away from the dens to feed and pursue other normal behaviors. Brumation is important in that it serves to protect snakes from winter freezing and is also necessary to reset snake reproductive cycles for the coming year. In short, dens are imperative for the conservation of virtually all snake species that brumate. Natural communal dens frequently confuse people into thinking that different snake species within are interbreeding or being eaten by other snakes. Neither of these thoughts have a factual basis. Various myths are associated with snake behaviors regarding movements towards and away from dens, as well as during brumation. Some people believe that emergence in the spring follows the first thunderstorm in which lightning strikes produce ground vibration to stir those restless serpentine souls! The Eastern or Black ratsnake, is called by some the Pilot snake, because it apparently guides rattlesnakes to dens and sometimes breeds with them there! In truth, both species are simply entering a communal den to overwinter.

2 Comments

|

Rattler TattlerAuthorsAdaptation Environmental Team: Bryon, Joe, and Kelly Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

|

Copyright © Adaptation Environmental Services L.L.C. circa 2012

|

Denver, Colorado

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed