|

Warmer weather makes venomous snake bites more likely, especially in spring, one study finds.

Most people know that snakes are ectotherms (cold-blooded), so when you think of climate change and warmer weather- snakes must like the heat, right? No, not necessarily. Snakes actually have a very specific temperature range that they prefer. Not too cold, not too hot. Yes, like Goldilocks. Warmer weather does tend to make snakes more active, but too warm and snakes will retreat to escape the heat. During July in the U.S., snakes are most active at dawn and dusk. If you are walking, hiking, biking or working outside during that time to escape the heat- be snake aware. When it comes to how snakes will adapt to alter their behavior due to climate change, scientists are not sure. But one study from GeoHealth, based in Georgia, is looking to find out how snake behavior is changing. "Climate change is not only making Georgia hotter but also increasing the likelihood of snake bite, according to [this] new study. Every degree Celsius of daily temperature increase corresponds with about a 6% increase in snake bites, researchers found.” One lead researcher from the study, Scovronick “speculated that the spring association could be because snakes "wake up" during that season, becoming more active and reproducing, while summer days could reach temperatures warm enough to slow snakes down. But that needs further exploration with species-level detail, he said. Other meteorological factors, such as humidity, had weaker or no associations with the rate of venomous snake bites.” As human development is expanding throughout the country, it is likely that snake-human interactions are going to increase. It is important workers and the public are properly educated. "Let people know what habitats snakes favor, such as places with dense groundcover, and they can be wary of such habitats. Snakes and people can live compatibly, even venomous snakes, as long as we respect and understand their habitats and needs." While more studies need to be conducted, it is possible that springtime may mean more activity for snakes across the U.S. Then, by mid-summer we may see less interaction. Once we enter late-summer, snakes will begin moving more often again as they move towards their hibernacula for the winter. American Geophysical Union. (2023, July 11). Warmer weather makes venomous snake bites more likely, especially in spring. ScienceDaily. Retrieved July 13, 2023 from www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2023/07/230711133302.htm Mariah Landry, Rohan D’Souza, Shannon Moss, Howard H. Chang, Stefanie Ebelt, Lawrence Wilson, Noah Scovronick. The Association Between Ambient Temperature and Snakebite in Georgia, USA: A Case‐Crossover Study. GeoHealth, 2023; 7 (7) DOI: 10.1029/2022GH000781

1 Comment

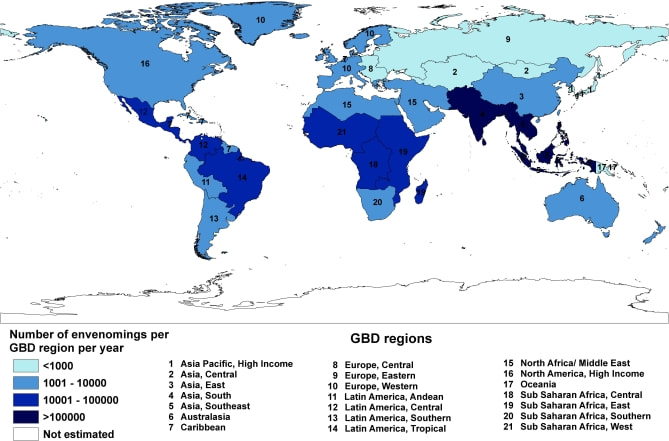

Outdoor jobsites are more likely to encounter venomous snakes. Specifically, construction workers are one of the top occupations most likely to encounter or get bitten by a venomous snake. It is important to treat the possibility of a snakebite as a workplace hazard. To be prepared, identify hotspots around the workplace. These are the top 3 places to look for snakes at a construction site:

The best way to prevent snakes from visiting your site is to keep a tidy yard and ensure rubbish and discarded materials do not pile up. It’s a good idea to ensure everyone is aware of the potential for increased snake activity after a long weekend or holiday break when the site has been quiet for some time. If you see a snake, stay clam and move away from the area slowly. Report the snake to a safety manager. We recommend that facilities that operate near venomous snake habitat have a trained team member that can properly move venomous snakes.  Prairie Rattlesnake, under construction debris. Photo copyright, Adaptation Environmental

A Plan to Reduce Snakebite Envenomations by 2030

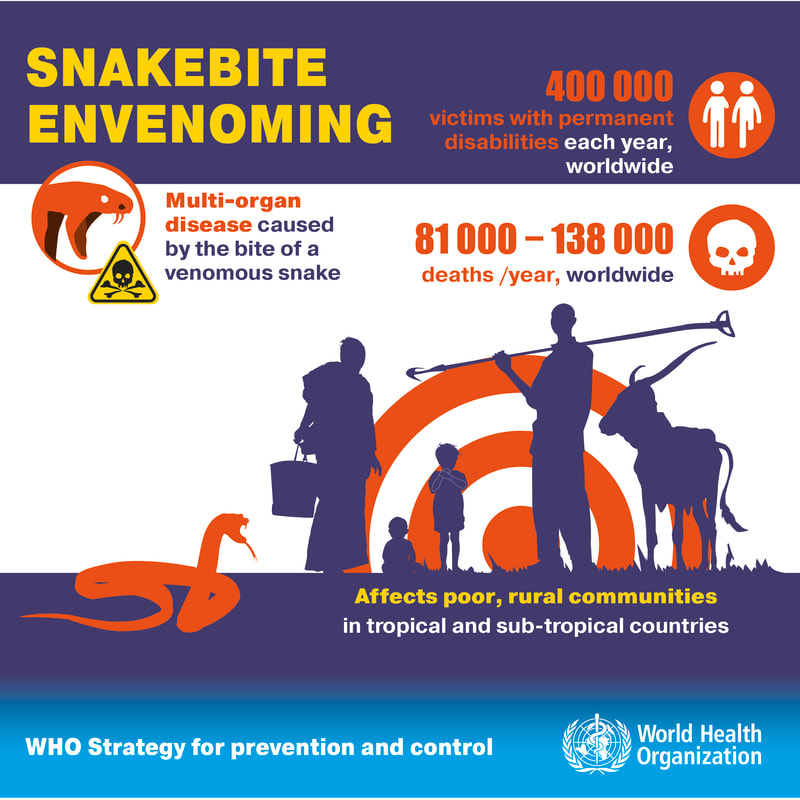

For millions of people around the world, the risk of snakebite is a concern as they complete daily activities. Snakebite envenoming is a neglected tropical disease (NTD) that affects people on every continent. Globally, snakebite envenoming causes about 81,000- 138,000 deaths each year. In 2019, the World Health Organization (WHO) developed a strategy to prevent and reduce snakebite envenomations by 2030. The goal of this initiative is to limit the number of disabilities and deaths that can result from a snakebite by 50%. The pandemic derailed the mission slightly, as priorities shifted, but WHO trying to get back on track. The Strategy In order to achieve their objective, the WHO has developed a comprehensive strategy. This strategy includes strengthening health systems, involving communities, utilizing resources to their fullest extent, and building meaningful partnerships. Effective and affordable treatment by healthcare professionals will play a big factor in achieving their goal, and will allow patients return to healthy lives after being treated. Part of this includes the availability and affordability of antivenoms to treat snakebite envenomations, which involves strengthening supply chains and supporting local production. Increased education among communities can be completed successfully through a variety of methods. Organizing workshops and training sessions that focus on snakebite prevention, identification of venomous species, and response techniques can be tailored for a variety of audiences with experts in the field. Developing educational programs in schools with engaging activities on snake awareness is beneficial for students even at a young age. A combination of all initiatives with the support of communities worldwide will help the WHO to reach their goal. WHO SNAKEBITE INFORMATION VIDEOThe Global Burden of Snakebite: A Literature Analysis and Modelling Based on Regional Estimates of Envenoming and Deaths

Kasturiratne, A., Wickremasinghe, A. R., de Silva, N., Gunawardena, N. K., Pathmeswaran, A., Premaratna, R., Savioli, L., Lalloo, D. G., & de Silva, H. J. (2008). The global burden of snakebite: a literature analysis and modelling based on regional estimates of envenoming and deaths. PLoS medicine, 5(11), e218. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0050218

In an all too familiar scenario, a rattlesnake has decided to escape the heat by entering someone’s basement through a crack in the foundation, unbeknownst to a homeowner. When the homeowner, we’ll call Larry, encounters the snake, he is confronted by a dilemma: Does Larry kill the snake to protect himself and his family or attempt to remove the snake and relocate it? Either scenario presents a challenge. Killing a rattlesnake in a house is not as easy as one would think. Larry would need to choose a proper tool for the task, one that would keep him a safe distance from the snake, assuming Larry is mentally up for the challenge of confronting an increasingly defensive venomous snake, which is responding to Larry’s series of rapid movements as he maneuvers around the snake. If Larry is not adept at dispatching the snake quickly, the difficulty of that task increases along with the risk of being bitten. Many people are unable to effectively judge a snake’s striking distance and may end up with an ankle or foot too close to the striking snake. Additionally, if the snake is killed, either involving decapitation of the snake or not, the fang and venom apparatus is still reactive to touch for a few hours, and can potentially result in envenomation from a theoretically dead snake. Another risk of attempting to kill a venomous snake is the possibility of the snake suddenly lunging away in a grand attempt of escaping Larry, who is moving rapidly around the snake, a behavior which further encourages elevated levels of defensive reaction. A second option is available in which Larry can opt out of the risks involved in the dispatching of the snake and instead work towards capturing the snake and releasing it some distance away from the house, perhaps less than a mile away. Ideally, Larry would select a capture container, such as a stout trash can with handles, and a long-handled tool, such as a rake or broom, and approach the snake calmly (assuming Larry still has a cool presence of mind). One of the advantages to a calm approach to live capture is that the snake may decide that Larry is not such a threat as once believed, so the snake adopts a calmer demeanor and thus, becomes a bit more cooperative for the capture attempt. This behavior will reduce the risks of snakebite, as well as the risk of escape into areas where retrieval of the snake is more difficult. The other advantage to live capture is the snake, in and of itself a highly efficient predator, can continue doing it’s job of helping to control rodent populations around Larry’s house, and Larry will have the satisfaction of not having to kill an animal when an alternative is potentially available. Of course, it wouldn’t hurt for Larry to investigate the opportunity to seek out training in the capture and relocation of a venomous snake or at the very least, locate personnel who are trained. If Larry is aware that venomous snakes exist near his house, he certainly has the incentive to seek out options for dealing with these snakes appropriately. For anyone who thoroughly enjoys thinking about complicated biochemistry, investigating the chemistry of snake venoms should be a priority! A discussion of differences in venom types is very complex, necessitating a basic overview of venom biology. The following post describes information focused on mainly snakes in the U.S. for reasons of simplicity and overall understanding. In the U.S., important venomous snakes are grouped in the family Viperidae, the vipers (i.e. viperids), specifically pitvipers, and Elapidae (i.e. elapids), specifically coralsnakes, which are cobra-related. In Colorado, only the pitvipers occur, elapids being found in Arizona, Texas, and seven states in the southeastern U.S. Pitvipers in the U.S. are comprised of rattlesnakes, cottonmouths, and copperheads, while the elapid group consists of 3 species of coralsnakes (SSAR). In comparing these two groups, venom differences occur based on different factors, such as types of prey, which contributes to complex combinations of venom chemical components.

Venom is basically a highly evolved derivative of saliva that certain snakes use primarily to subdue and secure prey. Secondarily, the application of venom can be a defensive tactic delivering negative feedback to a predator (or human). Venom in general is a magnificently super-complex poison sometimes exceeding 100 chemical components, consisting of proteins, peptides, and enzymes. Despite the small amounts that are injected into prey, there are severe, rapid changes that can occur to many of the body’s organ systems through cellular disruption. Components are frequently categorized according to the organ systems or cells that they affect, namely, cardiotoxins (affecting the heart), hemotoxins (destroying blood cells and vessels), myotoxins (disrupting muscle nerve impulses), and neurotoxins (primarily affecting muscles, especially those associated with breathing). These components can occur together in astonishingly variable amounts between families of venomous snakes, as well as species and even individuals within the range that they occur. Venom components are designed to work together in a complimentary way that amplifies the characteristics of each component. Let’s now look into pitviper and elapid venom group types and discover why they differ and how. With pitvipers, the diversity of prey types consumed is extensive, primarily consisting of mammals, but also including birds, lizards, anurans, and invertebrates. In order to be able to subdue and secure any suitable prey type by envenomation, there must be sufficiently complex and inclusive venom components available to cover all prey types. Most pitvipers have all four of the aforementioned basic component types in varying ratios, although a few pitvipers have neurotoxins as a dominant venom component, but still maintain the other components. After subduing prey, these components essentially initiate the process of prey breakdown, enhancing additional gastric digestion. Additionally, pitvipers possess amazing teeth, specifically the fangs, that inject appropriate amounts of venom into prey no matter the size. The fangs function as hypodermic syringes and are folded back into the upper jaw when not in use. In the elapid group, the prey choices of coralsnakes are somewhat more specific, smaller snakes and lizards being dominant on the menu. Coralsnakes have fangs as well, but because of a different skull structure, their fangs are short and fixed in place, not folding back as in pitvipers. Here, the action of injecting venom frequently requires a sustained chewing action to administer useful amounts of venom. Coralsnake venom contains very little cardiotoxin or myotoxin, instead, there is abundant neurotoxin, which functions to paralyze muscles, including muscles used in breathing. Apart from venom action on prey species, another significant difference between pitviper and coralsnake venom is the antivenom used to treat envenomations to humans and their pets. The same pitviper antivenom can be used with virtually all pitvipers in the U.S. However, a notable difference occurs in coralsnakes, where only an antivenom specific to coralsnakes can be used for envenomations by all of the coralsnakes in the U.S. While our most popular training course is our Venomous Snake Safety and Handling class for professionals. Professionals also need to know when to NOT move a snake. It is always safer NOT to handle a venomous snake. Know when to handle and when NOT to handle.

So, when does a snake NOT need to be moved or handled?

Most zoos are known for their diverse collections of animals from many countries for education, conservation, and the WOW factor. Zoos maintain a diverse collection of reptiles and amphibians, which includes venomous snakes from around the world. A great deal of responsibility is inherently required when a facility houses highly venomous snakes in a public setting. You can imagine that the safety factor needs to be ramped up to prevent escapes and therefore potentially deadly venomous snake bites to members of the public, as well as zoo personnel charged with caring for these snakes. How do zoos maintain a high level of safety? Let’s look at a typical set up.

In order to receive venomous snakes and house them in enclosures, zoos must have all of the necessary permits and inspections from various agencies assuring the public that all safety -related processes are being met. Simply receiving venomous snakes from delivery requires super safe containers that have redundant containers within containers. Explicit labels to identify container contents and displaying caution colors to avoid accidental unauthorized opening is always present. After safely opening the container, snakes are transferred to enclosures in a quarantine area to prevent any possibility of contagious diseases spreading to the main collection. Once cleared from quarantine, snakes are moved to exhibit enclosures. It is worth noting that in order for a zoo to maintain a venomous snake collection safely, part of their planned safety protocol is to keep antivenin at the zoo for each venomous snake for which antivenin is produced. Antivenin is kept in a refrigerator at all times and is replaced before it expires. Having antivenin on hand speeds up the response time to treat a venomous snake bite. Training zoo personnel to work with venomous snakes requires a process of repeated training to respond to a bite. Usually involving the entire staff in a snake facility, this process involves activating an alarm that sounds throughout the building to identify where the snake bite has occurred, enabling a faster response to the bite victim. The bite victim typically would remove the species identification tag from the enclosure and secure it to his body in case he becomes unconscious and is not able to identify the snake species involved. First aid at the onset may depend on the snake species involved. For example, a cobra bite may need a moderately tight compression wrap on the bitten extremity to impede venom flow while the bitten person is transferred to a hospital. Additionally, antivenin for that species is also transferred with the zoo personnel to the hospital. Antivenin must be given only under the charge of an experienced doctor under controlled conditions. Handling venomous snakes safely requires specially designed tools that are essentially extensions of our arms and hands. Snake handling requires safety training initially with non-venomous snakes for personnel new to snake handling. Training in the safe use of hooks and tongs and combinations of these tools goes hand in hand with the use of specially designed transfer containers used to temporarily house a snake while exhibit enclosures are maintained. Advanced training for venomous and non-venomous snake handling also incorporates the use of transparent plastic tubes in which a snake is encouraged to enter but restrained in a way that traps the snake inside the tube, preventing the head (and thus, the fangs) from extending beyond the tube. Tubing a snake safely is useful, although risky, but necessary for such things as visual inspections for medical reasons, determination of sex, administration of medications, measurement of length, etc. Snake restraint can also be accomplished using a squeeze box which uses a mesh lid to compress the snake into soft foam. Again, this technique also can be risky, which is why focused safety training by experienced venomous snake handlers is important. Techniques of snake handling are typically performed in small, controlled spaces which eliminates the potential for escape. Other safety equipment used includes face shields or handheld transparent shields for use with spitting cobras. Again, another handling risk requiring careful safety training. The prevention of snake bites in a zoo setting certainly is possible, but requires personnel to be inherently focused on safety training protocols along with regular snake bite response training. Knowledge and understanding of each species’ behaviors and potential for bites is key to safe snake handling and recognizing when not handling venomous snakes is prudent. Many of us are well aware of the methods by which birds and mammals endure the winter as endothermic or warm-blooded animals needing constant food to fuel body heat. These animals move constantly, searching for food. Alternatively, others simply go into a state of hibernation to save energy when food is unavailable. Snakes, being ectothermic animals, cannot generate their own body heat, or cool themselves through sweating, and must depend on their environment to help them adjust body temperatures according to changing needs of digestion or to escape from excessive heat or cold. So, what strategies can a cold-blooded, or ectothermic animal, like a snake employ to survive the winter cold? Snakes in temperate zones of the U.S. have no alternative but to go underground, using sites called hibernacula (singular—hibernaculum) or dens, to avoid freezing. While some mammals undergo hibernation in an inactive state to conserve energy, snakes go through a similar process called brumation, but differs in that, in some cases, movements of snakes in underground dens may still occur, as they take advantage of warmer sections within the den that shift during the winter. Indeed, some prairie rattlesnakes in more northerly temperate latitudes have been known to bask outside the entrance to their underground lair at times during warm spells in the winter!

How do snakes prepare for brumation? As the day length shortens and night time temperatures drop lower, snakes sense that cold weather is approaching and begin to move towards locations that they know from experience can provide them with a way to get underground below the freezing depth. During October, snakes stop feeding in order to clear the stomach of any food, which may typically take several days. Because snakes depend on the environment to heat their bodies to the proper digestion temperature, food must be processed out before the snake becomes too cool or it will simply rot in the stomach, often leading to fatal infections. The drive to seek out den sites becomes stronger with approaching cold weather, because cold snakes lose the ability to operate muscles that control movement and are in a race against time and freezing temperatures. Some snake species move considerable distances, perhaps up to a few miles, in a migratory push to arrive at a den in time. These den sites range from ant mounds, crayfish and earthworm burrows and rodent burrows, to spaces within subterranean rock strata, tree stumps, crawl spaces, old wells, and basements, to highlight a few examples. Natural dens in the landscape are selected based on characteristics that favor maintaining den temperatures at optimum levels, like south-facing cliffs or mountain slopes where the sun heats the soil longer during the winter. The same dens may be used every year or new ones are selected, and snakes of multiple species may use the same den, because this site could be the only spot within many acres that enables these animals to successfully avoid freezing. Thus, rattlesnakes, bullsnakes, and garter snakes, among others, will use the same communal den. Even snake-eating snakes may be present, because cold temperatures eliminate the desire for feeding. The numbers of snakes using dens may be as few as 3-6 or as many as thousands, as found in Red-sided garter snake dens in Canada. Den sites also provide snakes with some security from predation, when being cold prevents defensive action, although badgers and skunks have been known to dig them out. Additionally, snakes also depend on these dens to prevent dehydration, a common cause of overwintering mortality in juveniles. Baby and juvenile snakes have a particularly difficult challenge in detecting overwintering den sites, because they don’t yet have knowledge of where they are found. These young snakes may attempt to follow the scent trails of adults to den sites or, failing that, hope that they locate some underground passage that goes below the frost line and allows them another chance in the coming year. The amount of time spent in brumation is solely dependent upon how soon the next warming cycle begins in the spring and can last 3-9 months. In less than perfect underground microclimate conditions, this time in brumation sometimes results in many snakes, especially juveniles, succumbing to skin fungus or dehydration. With the warming temperatures of early spring, underground den temperatures also begin to rise, followed by snakes gradually edging closer to the den entrance. In most species of garter snakes, emergence from brumation is essentially explosive with intense reproductive copulation taking place almost immediately. Other snakes require more time to warm up the body physiologically before moving away from the dens to feed and pursue other normal behaviors. Brumation is important in that it serves to protect snakes from winter freezing and is also necessary to reset snake reproductive cycles for the coming year. In short, dens are imperative for the conservation of virtually all snake species that brumate. Natural communal dens frequently confuse people into thinking that different snake species within are interbreeding or being eaten by other snakes. Neither of these thoughts have a factual basis. Various myths are associated with snake behaviors regarding movements towards and away from dens, as well as during brumation. Some people believe that emergence in the spring follows the first thunderstorm in which lightning strikes produce ground vibration to stir those restless serpentine souls! The Eastern or Black ratsnake, is called by some the Pilot snake, because it apparently guides rattlesnakes to dens and sometimes breeds with them there! In truth, both species are simply entering a communal den to overwinter. Let’s begin by laying down some facts that we can sink our teeth into! There are very few species of snakes in Colorado that are considered dangerously venomous, which means that chances are that the snake you encounter next will be non-venomous, i.e., harmless to humans. Of the 30 or so species of snakes in Colorado, the good news is that only three are dangerously venomous! These three venomous snakes happen to be all rattlesnakes, but there tends to be a substantial amount of confusion in distinguishing rattlesnakes from other non-venomous snakes, despite all the information available. For example, the snake most commonly confused with rattlesnakes is the bullsnake, and this confusion transcends generations with repeated inaccurate information. Whether a newly hatched baby, juvenile, or adult, the myths associated with bullsnakes vs. rattlesnakes are clearly entrenched.

Let’s examine just a few commonly repeated myths for clarification. The first one states, “If the tail is rattling, it’s a rattlesnake”! Typically, all snakes vibrate or rattle their tail for different reasons. Usually, it happens when the snake is feeling threatened and wishes to either scare the offending threat away or, if an attack ensues, hopefully the tail will attract the brunt of the attack, and leave the head unscathed. In this way, the snake is more likely to escape with its life. If the tail vibration occurs in dry leaves or against an object that reverberates, the sound is amplified and may, in fact, mimic the rattle vibration of a rattlesnake. Watching the tail vibrate, you may notice that it is held close to horizontal in non-venomous snakes, while rattlesnakes tend to hold their tail vertically. It’s important to note that with rattlesnakes, the tail tip is usually composed of a series of segments or rattles that move when the tail tip is vibrated, creating that well known rattlesnake sound! Baby rattlesnakes only have one segment on their tail tip at first, so no sound is emitted, but the tail is still usually held vertically. In addition, rattlesnake tails are short and blunt, ending with rattle segments, while the tail in non-venomous snakes is long, with a gradual taper to only a sharp point. The second popular myth states, “Bullsnakes can breed with rattlesnakes, creating venomous bullsnakes”. When we look at the biology of this situation, we realize this event could not possibly happen, because bullsnakes are egg layers, and rattlesnakes give birth to living young, like mammals. It just doesn’t work! The third popular myth relates to a concept that states, “Bullsnakes chase away rattlesnakes”. Again, in looking at how these two snake species live out their lives in the same habitat, one can see that they go about life’s needs in entirely different ways, which reduces conflict and competition, allowing both snakes to co-exist. This concept may have had its origins in observing when both species occur together. Both are seen in the spring, but as the summer progresses rattlesnakes become more nocturnal, while bullsnakes may still be active when it’s not too hot. Separation of activity times may leave us with the impression that bullsnakes have indeed “chased” the rattlesnakes away! There are several other myths, but the myths described are the most often quoted. It may useful to note that bullsnakes are not typically snake eaters, so they would not have any influence on rattlesnake populations. So, just how does someone identify a bullsnake (or other non-venomous snake) from a rattlesnake? Because many snake species have a pattern of somewhat rounded or square-shaped, dark designs on their backs, including rattlesnakes and bullsnakes, this patterning is not a reliable identification tool. Instead, look at the tail and head. We have already discussed the tail differences, so let’s focus on the head. Bullsnake head shapes are barely triangular unless the snake is hissing at you (you’re too close!), while the neck width is nearly the same as the base of the head width. Much like looking at your thumb! Rattlesnakes have a strongly triangular head with a much thinner neck width relative to the base of the head. Moreover, each side of the rattlesnake’s face we find a pair of horizontal white stripes, akin to war paint! In addition, rattlesnakes tend to adopt a tight coiled posture at rest, different from other snakes. With the tail and head shape in your focus, you should be able to make a pretty reliable identification of whether the snake is a rattlesnake or not. As always, stay at least 3 feet away from the snake until you’re sure about your identification, still giving the snake some space, regardless. The autumnal equinox, or the first day of fall, is today! It’s a time when birds have already begun their gradual migrations to southerly, warmer lands, and our black bear is undergoing hyperphagia, a process of eating as much as possible to build fat reserves for winter survival. One has to wonder if the fall season affects other organisms, such as rattlesnakes, in any similar way. We know that in August, some rattlesnakes begin producing babies and also breeding in order to set up baby production for the next August. With this process overlapping into September, those snakes not involved with reproduction, like females that have already given birth and other non-breeding females, and males not breeding this year, will begin to step up their fall season food search in order to increase fat stores in advance of winter. The fall season feeding binge is also necessary to ensure future baby production, occurring every year and a half to two years. This feeding process helps all rattlesnakes get through winter hibernation underground by maintaining body health, and while the focus on feeding goes on, rattlesnakes are also gradually moving to denning locations in which hibernation takes place, locations sometimes used every winter. They must be in place to hibernate by early November to avoid freezing. Fall is a busy time for all snake species, even those which produce babies in the spring ahead of the rattlesnake’s schedule. The earlier breeding and reproduction still means that the fall season drives snakes to feed well and gradually begin to orient their movements to areas where hibernation takes place, just like the rattlesnakes do. Since snakes are active during the fall season, be sure to check out our snake safety tips guide. Written by Bryon Shipley Prairie Rattlesnake, Adaptation

|

Rattler TattlerAuthorsAdaptation Environmental Team: Bryon, Joe, and Kelly Categories

All

Archives

July 2023

|

|

Copyright © Adaptation Environmental Services L.L.C. circa 2012

|

Denver, Colorado

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed